Moholy Minaj

Chicago architects tend to take Mies as our daily bread. His aphorisms slip almost involuntarily off the tongue in critiques; his buildings loom over our Loop lunching, his curriculum continues to underpin our system of design education. Undeniably, Mies’ influence courses through the architect’s veins like the precisely aligned joints cut across the plaza and up the steely black facades of his Federal Center. His staid presence serves (as it does here) as an anchor within the shifting stylistic sea of 20th century architecture. While many of us are well-versed in the fairytale of his arrival in the Windy City, less are as familiar with a fellow Bauhaus transplant whose story unfolded in parallel: László Moholy-Nagy (pronounced muh-hoh-lee-noj).

Krueck + Sexton’s ongoing renovation of the Schatz Building in Chicago’s Streeterville neighborhood offered a chance to engage the legacy of this lesser known modernist. Initially constructed as a bakery, the 1917 masonry structure served as home to Moholy’s studio and American Bauhaus offshoot, the Institute of Design, from 1939-45 (concurrently with the renowned nightclub Chez Paree, which surely made for some creative and entertaining evenings). It was here that Moholy refined his Constructivist aesthetic, conducted early experiments in photography and light modulation, and integrated the sciences into a curriculum whose impact upon the graphic arts rivaled that of Mies’ IIT upon the field of architecture.

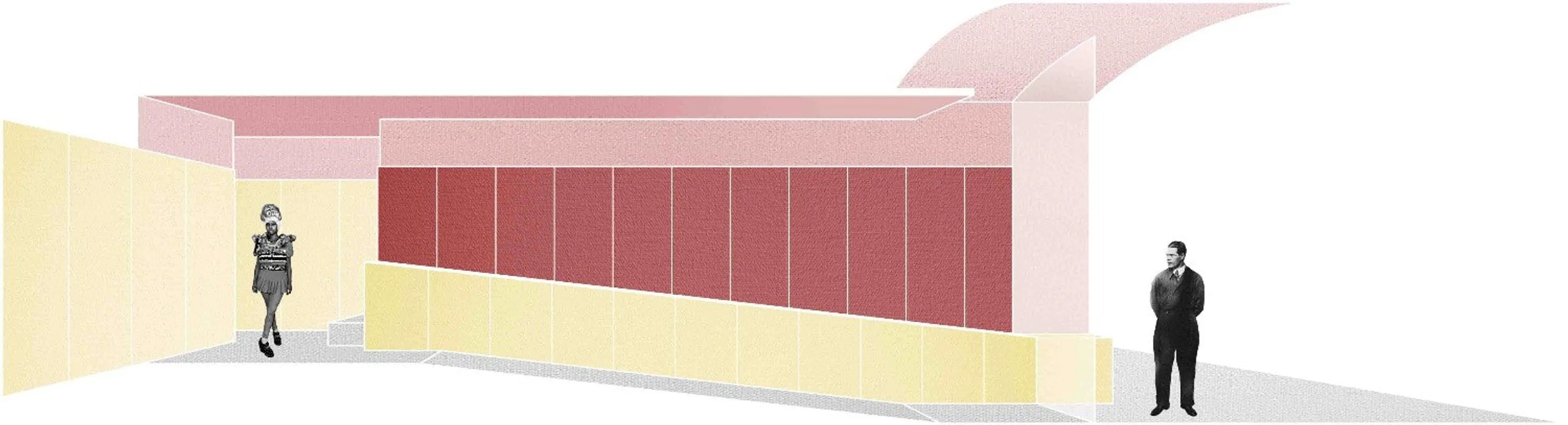

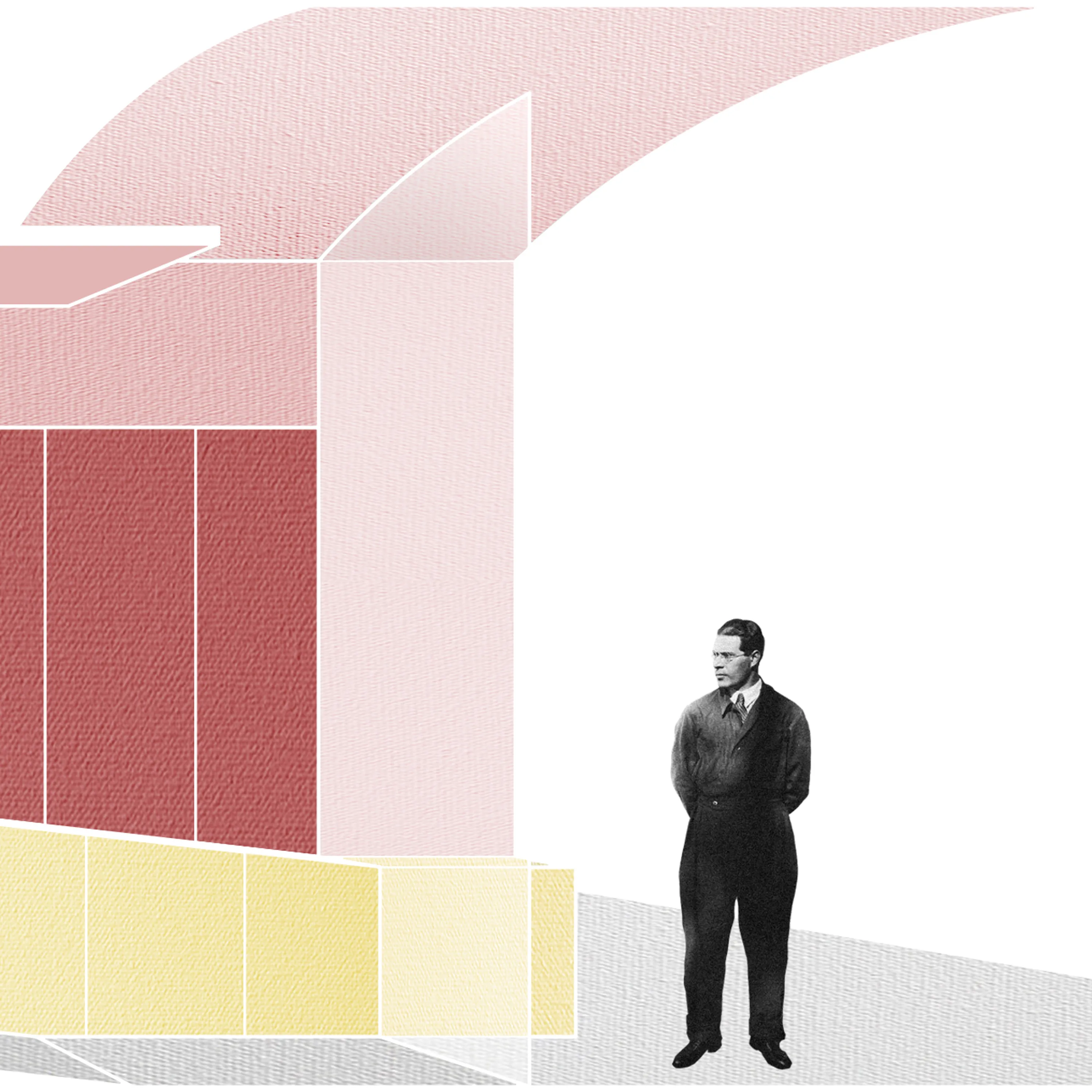

In the great tradition of architects [mis]interpreting and naively appropriating the aesthetic sensibility of artists, it was a melding of Moholy’s works that guided the design of the Schatz Building ground floor lobby and corridor. Planes and volumes are articulated as autonomous elements, glass panels generate depth and reflection, and pockets of luminosity create moments of intense contrast in reference to Moholy’s exercises in geometric composition, transparency, and modulation of light. It followed, then, that in representing the space we might further mimic the graphic principles of our man Moholy.

More than applying the colors, forms, and figures of his work, however, this representation subtly demands a deeper understanding of the artist by inserting his likeness into the image. Moholy stares into the spatial composition from outside, indicative of his temporal distance from the scene within. His fiery stare, however, betrays no surprise at the sight of the vaguely humanoid, Nick Cave-esque construct recognizable to 21st century folk as musician Nicki Minaj. All of this makes little sense without an understanding of Moholy’s prescience, for which I turn to an excerpt from Thomas Dyja’s book on postwar Chicago ‘The Third Coast’. Lucky for us, he cites our architectural anchor Mies as a point of comparison:

“If IIT and the Farnsworth House show Mies celebrating and guiding the industrial might of postwar America, in ‘Vision in Motion’ Moholy looked beyond the smokestacks into the post-industrial age where media had the power to alter man psychologically and physically. No other artist had Moholy’s comprehensive understanding of the issues that would inform art in the late twentieth century and well into the Digital Age. Art, he saw, was no longer about mysteries and inspiration; it was about tools and perception. The artist of the future wouldn’t be a genius, he’d be a witness, and his media would be the products of light- photography, television, and film… Control of the image was paramount.”

In this context, then, Minaj stands in as representative of a contemporary culture flooded by content. In her embrace of all image media (film, photography, fashion), her multiple identities (Female Weezy, Roman Zolanski, Rosa), and her synaptic rap artistry, Minaj is an exemplar of one consumed with- and by- the digital world. A man with “a million ideas a minute” (according to former student Katherine Kuh), Moholy too might have found himself quite at home in the information-inundated, image-infested, internet epoch. Even in the 1920's, however, he cautioned of a darker side to a society dominated by media:

“The danger of the photographic medium- including the motion picture- is not esthetic but social. It is the enormous power of mass-produced visual information that can enhance or debase human values. Brutal emotionalism, cheap sentimentality, and sensational distortion can, if they spread unchecked, trample to death man’s newly won ability to see gradation and differentiation in the light pattern of his world.”

Passing on the bait to interpret Moholy’s message in realms of greater ramification (cough, political), the question I pose is this: what is the role of architecture within this light-patterned insta-world?

While architecture may react by aligning itself with the fallacies of permanence and timelessness, it too cannot escape the reality of its matter as a product of light- albeit travelling at a different speed. Before one interrogates the flawed physical science of this statement, allow me to elaborate: Architecture will never lay claim to the instantaneous impact of the photograph; it will remain a rigorous and time-consuming undertaking. Nor will it ever wield the emotional precision of film; its users will inevitably determine its valence. It can, however, rely upon its superior degree of immersion and broad appeal to the senses; the play of shadows upon a plane of glass fascinates the eye, the resonance of a cathedral nave fills the ears, the fragrance of a cedar-clad cabin tickles the nostrils, the roughness of a bonded brick wall invites the hand’s touch. It is this relationship to the senses, however, that means architecture too is subject to sensational distortion. As we design, then, let us be conscious and committed to the values that we embed within our work (lest they be engineered out).

Architecture alongside the rest of the media: undeniably powerful in its cultural capacity and social significance, yet ultimately more ethereal than eternal...

Links

http://www.miessociety.org/legacy

http://www.ksarch.com/

http://www.theschatzcompanies.com/#home

http://www.moma.org/collection/artists/4048

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicki_Minaj

http://nickcaveart.com/Main/Intro.html

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lyGivD8aJi4

Sources

Dyja, Thomas. The Third Coast: When Chicago Built the American Dream. New York: Penguin, 2013. Print.

Moholy-Nagy, László. Vision in Motion. Chicago: Theobald, 1947. Print.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicki_Minaj

Images

http://www.iconofgraphics.com/laszlo-moholy-nagy/

http://www.moma.org/collection/works/54392?locale=en

http://www.penccil.com/gallery.php?p=460290059689

http://francesarcher.com/2011/08/oh-i-love-the-night-life/

Eli Logan

Intern Architect